There’s a huge market for humanely-marketed, animal-derived food. As factory farming has entered the popular consciousness — despite the desperate but pervasive success of ag-gag legislation [1] to shield us from exposure to the realities of the supply chains that end up feeding most of us — labels like Certified Humane have risen in popularity.

These labels allow us to continue normalizing farm animals as more property than animal. As property, they’re not as worthy of the implicit respect we give to companion animals, even when their sentience is obviously similar. This is especially evident in environments, like animal sanctuaries [2], where they are able to express the fuller breadth of their personalities.

An animal considered property cannot be certified humane. If we broadly care about animals as companions, we should also care about the nature of the lives that farmed animals are being forced to live. Typical predators, and even most human hunters, go for the quickest possible kill. Breeding animals into existence in order to exploit their bodies has outgrown and outbred the purpose it may have originally held for people with a lot more land and much different animals.

Hidden in the open – the grass-fed nightmare:

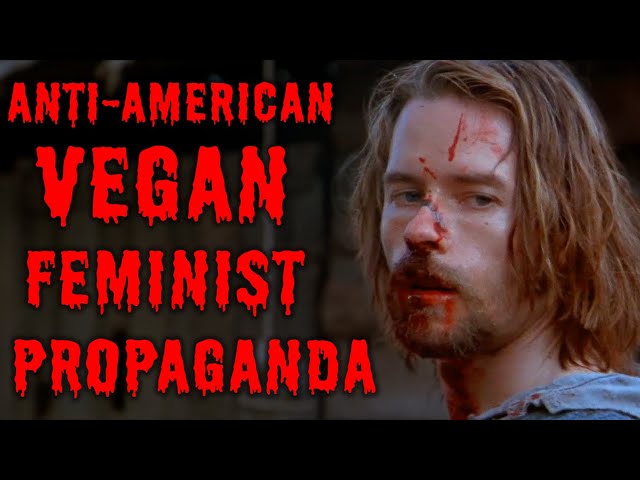

While some dairy products are marketed as coming from grass-fed and pasture-raised cows, these cows are still bred to produce abnormal quantities of milk:

The average amount of milk per cow has shot up since 1950. There are fewer than half as many dairy cows in the United States as there were back then, but now they produce almost twice as much milk. [3]

A single dairy cow’s udder can hold between 3 to 6 gallons of milk at a time. On average, they can produce around 8.39 gallons or 134 cups of milk per day. [4]

Image: a graph showing the amount of milk produced per cow, which increased 550% from about 4000 gallons in 1924 to about 22,000 in 2015.

Carrying around this much milk has its consequences for the cows, which manifest as regular sources of pressure and pain. The Farm Animal Welfare Education Center writes:

Dry-off procedures are associated with engorgement of the mammary gland resulting in udder discomfort and pain, which are likely to be more pronounced in high-producing and abruptly dried cows. At dry-off, the mammary gland continues to synthesize and secrete milk, resulting in an increased intramammary pressure that may cause pain and discomfort for the cow.

Currently, dry-off involves the cessation of milking in cows that are still producing significant quantities of milk yields such as 20–35kg/day and in some cases up to 50Kg/day. The risk of discomfort associated with udder engorgement at dry-off is higher in high-producing cows.

[…] Some farms prefer to decrease milking frequency several days before drying-off to reduce milk yield. However, there are some evidences [sic] that this practice may still cause some discomfort due to udder distension. [5]

In order to produce profitable quantities, dairy cows are forced to become pregnant through artificial insemination:

One of the reasons for this huge rise in milk production is the introduction of artificial insemination. “We went from natural breeding of cows to artificial insemination of cows, and that let us have better genetic selection of animals than just, you know, what’s your best looking bull out of the herd that used to be,” said Stephenson, director for dairy policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin Center for Dairy Profitability. [3]

Image: cows at Ever-Green-View farm in Wisconsin. Three cows look at the camera from across a feeding stall, a fourth cow visible in the background.

This surprise pregnancy is, of course, as huge an ordeal for the cow as it would be for any human, and this happens multiple times per cow. The calves from each of these pregnancies are brought to term, since the cows will not produce milk otherwise, and separated from their mothers either immediately (or within 24 hours if they’re lucky enough to be born on a smaller farm). Here is the life of a Stauffer Dairy cow in Washington State, as described by Krista Stauffer on her blog The Farmer’s Wifee:

A cow gives birth to a calf. It’s a girl also known as a heifer or a boy known as a bull. That calf is in fact taken away from its mother within 24 hours. The calf is given colostrum & raised on milk to 90 days on our farm. The time on milk varies from farm to farm. At 12–15 months the heifer is placed with a bull. Most farms in the U.S. use artificial insemination. At about 2 years of age that heifer will give birth to her first calf. [6]

I noticed no mention of what happens to the bulls that are born. Since half of these calves are inevitably male and unable to replace their mothers as milk cows, I found that it’s industry standard to either kill them at birth — since they’re not worth raising for beef — or sell them off to a veal farm, where they spend the rest of their short lives in a state of hyperconfinement so that their muscles stay soft in order to achieve the texture veal is known for. As Hemi Kim reports for Sentient Media:

Although the guidance requires calves to be able to stretch and lie down, they are still confined to spaces not much bigger than their bodies. [7]

Mother cows have been observed calling for their missing calves at all hours of the day and night [8], and the calves that grow up to become dairy cows themselves suffer psychological consequences from this separation. As Dave Rogers reports for The Daily News of Newburyport:

Calves of dairy cows are generally separated from their mothers within the first 24 hours after birth. The majority of the milk thus enters the food market and not the stomachs of the calves. However, growing up without a mother has consequences.

Scientists at the Vetmeduni Vienna studied the long-term effects of early maternal deprivation. Their study shows that calves which have contact to their mothers or to other cows during rearing become more sociable adults. [9]

But what else happens to the mother cows and the female calves that grow up to replace them? Stauffer Dairy says:

The average age of a dairy cow in the United States is 5 years old. That doesn’t seem very old for a cow now does it? The average life of a dairy cow “should be” 15–20 years depending on your source.

[…] Animal rights extremist[s] would have you believe that this cow will only stay on the farm until her second or third lactation because of her poor health. This is not true. Note: When a dairy cow leaves the herd to enter into the beef supply she is sold as a “cull cow”. [6]

So she becomes beef after about 5 years of being forcibly impregnated instead of living her typical lifespan of 15–20. What are the other reasons?

The cow will not breed. A cow has to produce a calf in order to produce milk. The cow could be perfectly healthy & still be infertile.

The cow does not produce enough milk to cover the cost to feed her. Again, this doesn’t mean the cow is unhealthy. It simply means her milk supply doesn’t cover the cost of her feed intake. [6]

Cold and utilitarian, but expected. It’s a for-profit dairy farm, not an animal sanctuary. What else?

The cow could have hoof issues. Does this mean the cow is unhealthy? Nope, just means she is needing constant attention. This could include visits from the local hoof trimmer or vet.

The cow could have issues with mastitis. Each cow is different, as some will never have mastitis, some could have it once in their life & others could have chronic issues with mastitis. There are cases that can be treated successfully. There are cases that will go away & come back. These cows are removed from the herd. [6]

Neither of those things sound good. Can we revisit that in a minute?

The cow has undesirable traits. What does that even mean? Well a cow could possibly come from a cow that wasn’t a very good milk cow. The mother could have passed down hoof issues, a not so nice udder, poor milk production, etc. [6]

Image: cows on Stauffer Dairy’s farm — as high-end as it gets for a dairy cow. They recline in rows of small resting areas inside of a barn with large brick pathways.

Cows are bred to produce as much milk as possible, even on smaller farms, but why are hoof issues and mastitis so common? Ernest Hovingh from the Penn State Veterinary Extension Team at the Department of Veterinary & Biomedical Sciences writes:

Dealing with the hoof health situation in a herd involves a strategic and comprehensive approach. Simply hiring a professional hoof trimmer to come in and trim cows, even if the visits occur on a regular and frequent basis and the trimmer is highly competent, is not adequate [emphasis added]. Similarly, a quest to find the ‘best’ concoction for a footbath solution, even if it is successful, will seldom be enough to solve a herd’s lameness problem. [10 - PDF]

That’s not good. If regular visits from the trimmer aren’t enough, what can be done about it? Ernest continues:

Knowledge about the various factors that put a cow at risk of becoming lame is critical in order to prevent lameness. Research and experience have shown that the interaction of many different factors is responsible for determining whether or not a dairy cow becomes lame, and if so, whether she becomes mildly, moderately, or severely lame.

The relative importance of these factors, and the way they interact, varies from farm to farm, and even from season to season within a farm. Therefore, awareness of these risk factors, and how they can be ameliorated, will help farmers, veterinarians, hoof trimmers, and other consultants minimize lameness in their herds. [10 - PDF]

While admitting that knowledge about the various factors that put a cow at risk of becoming lame is critical in order to prevent lameness, this paper focuses on ways to identify and manage lameness in a timely manner once it occurs — not how to actually prevent it. The exception is a section on types of flooring.

Similarly, the cause of mastitis as a bacterial or fungal infection is often discussed, but how to actually prevent it is an issue that is presented as a multifacted welfare problem with no direct solution. Ecological Agriculture Projects from McGill University writes on the various ways to treat mastitis without antibiotics:

Mastitis is a difficult problem to comprehend because it is a disease caused by many factors. Microorganisms are responsible for the infection, but for them to enter the mammary glands and establish themselves to the point that they cause an infection, a multitude of factors may be involved (e.g. hygiene, housing, climate, milking machines, feed, genetics) acting simultaneously. It is even more difficult to generalize about the relative importance of each one, as certain factors affect certain microorganisms. [11]

Health issues, it seems, are systemic to the industry, and seen as a cost of doing business, since palliative solutions are enough to keep milk moving.

"Free range" is strange:

In the egg industry, hens have been bred to lay 20x the eggs of their wild junglefowl ancestors and cousins. Wild junglefowl lay about twelve a year [12 - PDF], while the hens we’ve bred lay 200 to 300. Male chicks that can’t become a part of this cycle, thankfully, can avoid being born due to a technology called in-ovo sexing. The hens that get to spend their lives laying that many eggs, however, undergo significant physical strain from the output, including “cage layer fatigue” [13] from chronic calcium deficiency due to being unable to recover from their feed the full amount of calcium they use laying eggs, which are usually eaten by the hen if they’re unfertilized.

Image: a ‘free range’ turkey supplier for Whole Foods from Speciesism: The Movie (2013). A giant warehouse of turkeys is seen from the inside with a mechanical feeder.

So what’s this about "free range"? Here is how the nonprofit Certified Humane describes it:

Free range (or free roaming) is a general claim that implies that a meat or poultry product, including eggs, comes from an animal that was raised in the open air or was free to roam. Its use on beef is unregulated and there is no standard definition of this term. “Free Range” is regulated by the USDA for use on poultry, only, (not eggs) and the USDA requires that birds have been given access to the outdoors but for an undetermined period each day. USDA considers five minutes of open-air access each day to be adequate for it to approve use of the “Free Range” claim on a poultry product. “Free range” claims on eggs are not regulated at all. To learn more about what is meant by this term, consumers must contact the manufacturer. [14]

The hens that lay the industry’s cheapest eggs only live to be one to two years old [15], and — unless they meet the stricter standards of labels like Certified Humane — are debeaked as chicks to prevent them from pecking their fellow flock members’ feathers out, or straight up cannibalizing each other. Yes, to prevent them from using their naturally sharp beaks to tear each other to shreds and eat each other. Here’s what Certified Humane allows instead of debeaking:

Research shows that in flocks of over 60–120 birds, feather pecking may quickly affect a large proportion of the flock, causing significant pain and suffering. HFAC allows minimal beak trimming in order to avoid heavy feather pecking and cannibalism among laying hen flocks [emphasis added]. [16]

Producers will be required to phase out beak trimming/tipping as soon as the causes of cannibalism and ways of preventing it have been identified. [17 - PDF]

In order to be Certified Humane, only the behaviors of feather pecking and cannibalism need to be prevented — not whatever underlying stress is causing these behaviors to emerge. There are 40 “leading animal scientists, veterinarians, and producers” [17 - PDF] in the Humane Farm Animal Care’s Scientific Committee, and none of them understand why these birds want to kill each other.

Meat chickens, on the other hand, are bred separately to grow very quickly in a short amount of time, slaughtered before their heart issues kill them. As Jennifer Mishler reports for Sentient Media:

Today, a factory-farmed chicken, or “broiler chicken,” is typically slaughtered for meat at somewhere around 45 days old. It wasn’t always that way.

According to the National Chicken Council (NCC), in 1925 it took a broiler chicken an average of 112 days to reach a market weight of 2.5 pounds. As of 2019, the market weight has soared to 6.32 pounds — and a chicken reaches market weight much faster, usually around 47 days, or about the same amount of time it takes to grow a bunch of kale.

Young chickens now grow so large, so quickly that undercover investigations consistently find birds barely able to move or stand. Some birds are so crippled by the additional weight that they are unable even to survive long enough to be slaughtered. Many birds will not live to see their two-month birthday. [18]

Image: a chicken destined for Costco (Siphiwe Sibeko via Reuters). They are contrasted sharply against a blurry crowd of their kin, an alert eye looking in the direction of the camera lens.

Humanity:

We exist on a continuum with animals and are ourselves animals. The more I’ve learned about our relationship to animal farming, the more I’ve come to believe that our ability to dehumanize each other comes from the same place as our ability to depersonalize animals.

There also seems to be a selective empathy gap when we consider companion animals more worthy of our grief than the animals we farm, who — if given the chance to fully express their personalities — would match our cats and dogs for emotional complexity and intelligence.

Instead, they are traumatized, and the limited expression of personality that results from that trauma becomes the justification in the cultural consciousness to consume what’s perceived to be a lesser animal — nothing like the creatures we consider family. That is, we are far more willing to consider a dog, cat, or parakeet our family member than we are a cow, pig, or chicken.

Of course, it’s a lot harder to take care of a cow or a pig when we’re used to thinking of them as food, but that’s the point, isn’t it? If we think these animals deserve affection at all, we outsource it to the farm and slaughterhouse workers who we don’t really know and place blind trust in with our dollar. But farm conditions aside, what’s affectionate about a slaughterhouse?

The condemned:

We have to take an honest look at what we are condemning so many animals to experience, especially once that dairy cow reaches killing time and is sent in a truck to a slaughterhouse. Hemi Kim writes:

Because slaughterhouse workers are trying to create the most efficient workplace possible, they adopt cruel ways of speeding things up. When you’re dealing with thousands of cows or pigs that must all be slaughtered quickly, the last thing you want is a bottleneck as the animals are ushered to their imminent death.

Slaughterhouse workers use stun guns and cattle prods to shock and beat their animals into submission. If a cow is walking too slowly or a pig tries to run away, the workers will shock the animals into obedience. [19]

The North American Meat Institute’s guidelines, which the Certified Humane label follows, admit that electric prod use is basically inevitable:

A well-designed plant that has eliminated distractions and other handling impediments can greatly reduce electric prod use, though it is difficult to eliminate it entirely. [20 - PDF]

It's hard on the slaughterhouse workers, too. From the BBC piece "Confessions of a slaughterhouse worker":

Emotions in the abattoir tended to be bottled up. Nobody talked about their feelings; there was an overwhelming sense that you weren't allowed to show weakness. Plus, there were a lot of workers who wouldn't have been able to talk about their feelings to the rest of us even if they'd wanted to. Many were migrant workers, predominantly from Eastern Europe, whose English wasn't good enough for them to seek help if they were struggling.

[...] Abattoir work has been linked to multiple mental health problems — one researcher uses the term "Perpetrator-Induced Traumatic Syndrome" to refer to symptoms of PTSD suffered by slaughterhouse workers. I personally suffered from depression, a condition exacerbated by the long hours, the relentless work, and being surrounded by death. After a while, I started feeling suicidal.

It's unclear whether slaughterhouse work causes these problems, or whether the job attracts people with pre-existing conditions. But either way, it's an incredibly isolating job, and it's hard to seek help. When I'd tell people what I did for work, I'd either be met with absolute revulsion, or a curious, jokey fascination. Either way, I could never open up to people about the effect it was having on me. Instead I sometimes joked along with them, telling gory tales about skinning a cow or handling its innards. But mostly I just kept quiet. [21]

Michael Lebwohl in the Yale Global Health Review called for the psychological harm of slaughterhouse work to be addressed:

[A] lot of guys at Morrell [a major slaughterhouse] just drink and drug their problems away. Some of them end up abusing their spouses because they can’t get rid of the feelings. They leave work with this attitude and they go down to the bar to forget.”

These stories echo those of combat veterans and survivors of disasters who suffer from stress disorders. The need to dissociate from reality to continue with their work leads individuals down a path that some may term “pathological”. [22]

These comments from Krista Stauffer’s blog [6], in this context, are heartbreaking:

Jessica: I love the statement “They are not humans and do not have to same rights as humans.” I think so many people think they do in fact deserve to be treated as humans when in fact they are livestock. Livestock should be treated with the best possible care but at the end of the day the are animals.

Stephanie L.: I have walked out of the barn crying many mornings when the cattle man comes.

Shari Klasse: I think I have walked out of the barn crying or just stay away every time the cattle hauler comes. I just get too attached to my cows.

This one and its reply are particularly heartbreaking:

Vicki Bauman: Are there no sanctuaries where these cows can go? Why do they have to be slaughtered? If they have served well in the dairy industry why can they not be retired?

Krista Stauffer: People consume meat, that will never change. They help feed this growing population. The cost to feed cows is incredibly high. I guess if you could find someone that is incredibly wealthy and has nothing better to do with their time, maybe they would take them? Chances are, that is not going to happen.

Normalization & alienation:

The intensive breeding of animals in captivity for the sole purpose of turning them into food (and non-food products) is an exceptionally morbid meta to have normalized. We have been encouraged to objectify animals while the consumption of their bodies has been hypernormalized.

We have been shielded from having to consider the pain these animals are going through. We’re ultimately trusting brands, especially ones that promise to be humane, but we keep being shown that humane is far too generous a term for what these animals end up being forced to go through. Abusive conditions will persist for as long as we continue to objectify animals, because that objectification creates the foundation for neglect.

Going plant-based is an alienating experience. Animal products from the worst parts of the supply chain are marketed everywhere you turn in any major city. Emerging from this hypernormalization is not easy, and no one should expect it to be, but awareness of the agony happening behind the pastoral marketing is crucial for us to process. And the more of us process this reality, the easier it will be.

Recommended media:

Speciesism: The Movie (2013) is a lighthearted but serious piece of investigative journalism disguised as a documentary. It explores through broad-ranging interviews and visits to animal farms (and a sanctuary) the question of what speciesism is and whether filmmaker Mark Devries can find an excuse to keep eating animal products. [23]

Mark Devries asks:

So if you’re saying that members of other species can feel, experience emotions — maybe even more intensely than humans — what does that mean?

James Serpell, PhD, Dept of Veterinary Science, UPenn responds:

Well, it means that we grossly underestimate the extent to which animals may be suffering. From an ethical standpoint, we need to give them the benefit of the doubt.

Image: a view of a high-intensity pig farm's rows of elongated buildings from above, two waste lagoons visible next to them.

That means we underestimate fish, too. Fish, it turns out, are playful, thinking creatures, even without the prefrontal cortex we usually associate with higher-order intelligence. Far from being the unfeeling, alienlike automata they are often portrayed to be, fish are actually who we inherited — as members of the animal kingdom with central nervous systems — our sense of being conscious from. [24, 25]

Image: a pile of dead fish with the caption, "typically, fish are killed by asphyxiation."

Image: the same pile of dead fish from another angle with the caption, "it can take hours for them to suffocate to death."

From Hannah Bugga for ChooseVeg:

Cow is a heart-wrenching documentary that tells the tale of Luma, a cow used for milk. The footage was shot over four years at a rural farm in England and shows the relentless cycle of mental and physical suffering cows endure at dairy farms. […] Viewers experience the entire film from the point of view of the mother cow as her body deteriorates through years of exploitation. [26, 26.1]

Image: a cow in an enclosure looking toward the camera intently with a quote from Screen magazine's review of the film: "nearly wordless, but extremely loud."

Earthling Ed writes:

[Humanewashing] is essentially the same as greenwashing, but instead of trying to make you think that their products are sustainable, it’s a tactic the meat, dairy and egg industries use to try and convince you that their products are ethically produced and good for the animals they raise and kill. [27, 27.1]

Image: a blurry, pastoral photo where a chicken can be seen roaming behind the crisp, superimposed logo of a happy, cartoon chicken prancing in front of a cartoon egg above the words "the happy egg co" in all lowercase.

Elwood's Organic Dog Meat is vegan agitprop in the form of a parody dog butcher website that serves to draw a comparison between the animals we farm and the animals we keep as companions. Content warning: there are pictures of butchered meat. [28]

Image: the logo for Elwood's Organic Dog Meat with the caption "delicious dog since 1981. Farm Fresh." A cartoon cowboy is seen lassoing the sillhouette of a more realistic cowboy lassoing the sillhouette of a dog, with a cartoon piece of what is presumably dog steak with an American flag sticking out of it next to them.

Overanalyzing Ravenous by Atun-Shei Films is a documentary that explores, through an analysis of the 1999 movie Ravenous (directed by Antonia Bird), the connection that has been forged in the psyche of the colonialist man between manhood and eating meat. [29]

Image: the thumbnail for "Overanalyzing Ravenous" by Atun-Shei Films, showing a closeup of a long-haired white man from the film looking off screen, covered in blood.

Don’t be afraid of tofu:

There’s a myth that the phytoestrogens, or isoflavones, in soy products are powerful enough to wreak havoc with the human endocrine system. Luckily, this is not the case, and these isoflavones have demonstrated numerous health benefits. From the Harvard School of Public Health:

Results of recent population studies suggest that soy has either a beneficial or neutral effect on various health conditions. Soy is a nutrient-dense source of protein that can safely be consumed several times a week, and is likely to provide health benefits — especially when eaten as an alternative to red and processed meat. [30]

Soy crop:

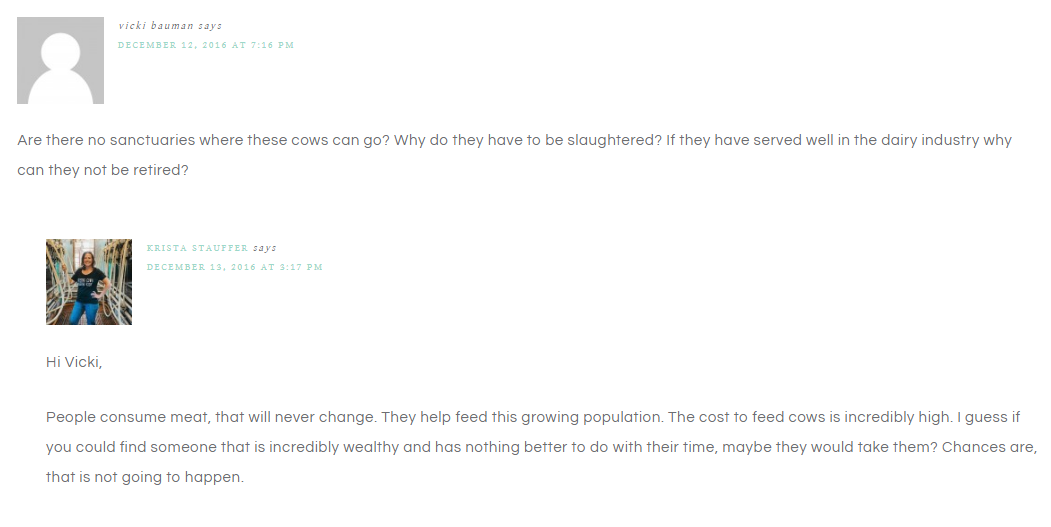

According to Our World in Data, between 2017 and 2019, 76% of the world’s soybeans were processed into feed for livestock, while only 20% became human food. There is certainly room, within existing soy cropland, for a shift in that demand, should we develop an appetite for the very crop we feed so much of our livestock.

Image: a breakdown of global soy allocation into the categories of direct human food (20%), animal feed (76%), and industry (4%).

Vegan recipes:

For recipes, check out these websites (thank you Alex ♡):

References:

- New Solutions – “Ag-Gag” Laws: Evolution, Resurgence, and Public Health Implications

- Earthling Ed – Surge Sanctuary, where we're at now.

- Wisconsin Public Radio – How We Produce More Milk With Fewer Cows

- Dairy Farming Hut – How Much Milk Can A Cow’s Udder Hold?

- Farm Animal Welfare Education Center – Udder Pain and Discomfort at Dry-Off in Dairy Cattle

- The Farmer’s Wifee – Average Age of a Dairy Cow

- Sentient Media – Inside the Veal Industry: Where Dairy Calves Go to Die

- The Daily News of Newburyport – Strange noises turn out to be cows missing their calves

- University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna – Early separation of cow and calf has long-term effects on social behavior [sic]

- Dept of Veterinary & Biomedical Sciences, Penn State University – Lameness, Hoof and Leg Issues in Dairy Cows (PDF)

- Ecological Agriculture Projects – Treating Mastitis Without Antibiotics

- The Humane Society – About Chickens (PDF)

- Poultry Science – Influences of low level of dietary calcium on bone characters in laying hens

- Certified Humane – “Free Range” and “Pasture Raised” officially defined by HFAC for Certified Humane label

- HuffPost – Here’s What Farms Do To Hens Who Are Too Old To Lay Eggs

- Certified Humane – Beak Trimming

- Humane Farm Animal Care – Animal Care Standards — February 1, 2018 Standards — Egg Laying Hens (PDF)

- Sentient Media – Outgrowing the Chicken House: A Brief History of the Modern Broiler Industry

- Sentient Media – Slaughterhouses: The Harsh Reality of How Meat Is Made

- NAMI – Recommended Animal Handling Guidelines & Audit Guide: A Systematic Approach to Animal Welfare (PDF)

- BBC – Confessions of a slaughterhouse worker

- The Yale Global Health Review – A Call to Action: Psychological Harm in Slaughterhouse Workers

- Speciesism: The Movie

- NowThis – What Fish Feel When They Are Killed for Food

- Peace By Vegan – How Conscious Can A Fish Be?

-

ChooseVeg – New Documentary Cow Brings Cannes Film Festival Audiences to Tears

- COW – Official Trailer

-

Earthling Ed – Greenwashing? It’s time to talk about humane washing

- Wikipedia – Greenwashing

- Elwood's Organic Dog Meat – Frequently Asked Questions

- Atun-Shei Films – Overanalyzing Ravenous

- Harvard School of Public Health – The Nutrition Source: Straight Talk About Soy